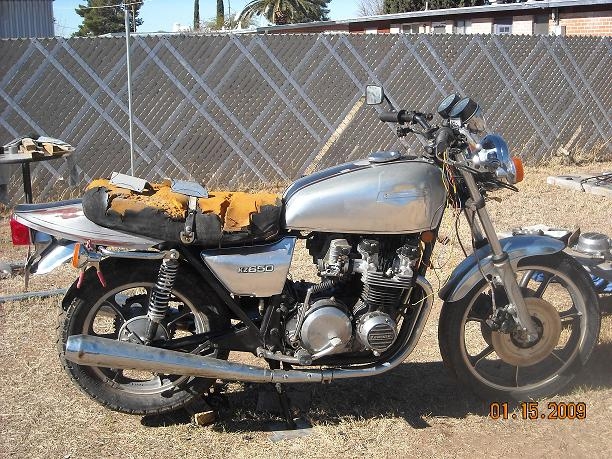

Kawasaki Z650 1976

| Основная информация |

| Модель: |

Kawasaki Z650 |

| Год: |

1976 |

| Тип: |

Спорт-туризм |

| Двигатель и привод |

| Рабочий объем: |

652 см3 |

| Тип: |

Четырех цилиндровый рядный |

| Тактов: |

4 |

| Мощность: |

66.00 л.с. (48.2 кВт)) @ 8500 об./мин. |

| Компрессия: |

9.5:1 |

| Диаметр х Ход поршня: |

62.0 x 54.0 мм (2.4 x 2.1 дюймов) |

| Клапанов: |

2 |

| Контроль топлива: |

DOHC |

| Охлаждение: |

Воздушное |

| Коробка передач: |

5 скорости |

| Привод: |

Цепь |

| Скорость и ускорение |

| Макс. скорость: |

190.0 (118.1 mph) |

| Прочее |

| Вместимость бензобака: |

16.5 л. |

| Передняя покрышка: |

3.25-19 |

| Задняя покрышка: |

4.00-18 |

| Передний тормоз: |

Один диск |

| Задний тормоз: |

Барабанный |

On the road the bike gives away nothing in performance

and is far and away a better performer than 550 cc machines. Flat-out mean

top speed at MIRA was 119-6 mph, only 4 mph down on Suzuki's GS750 and 2

mph less than the Honda CB750F1.

Even more stunning is its acceleration. Taking to the test track like a

drag racer, the Z650 scorched through the quarter-mile in 12-9 sec with a

terminal speed of 101-6 mph. Although eight runs were timed, six of which

were 13 sec or under, the bike finished as unruffled as ever.

The secret is not only the power of the twin-cam 652 cc short-stroke,

four-cylinder engine, but the bike's perfect gearing and balance. The

Z650's wheelbase is neither so short as to provoke unmanageable wheelies on

take-off nor so long that there is too much wheelspin.

Drop the clutch at 7,000 rpm and the Kawasaki just digs in and gets on with

the job, the front wheel just hovering above the tarmac for the first few

yards. It is as though the bike was made for drag racing. The proof of this

is that the Z650 is one of the quickest bikes from rest through 110 yards.

The terminal speed of 66-8 mph has only been beaten once - by the

super-fast 1973 Kawasaki Zl 903 cc four at 68 mph. It can reach 50 mph in

just 3 sec from rest.

Yet the bike is no awkward rev-happy racer. Although it can scream up to

10,000 rpm (the red line is at 9,000 rpm), the engine is sweet and flexible

enough to haul along at under 4,000 rpm and there is torque enough to give

a sizeable kick in the seat as you open up.

Apart from a band around 7,000 rpm, the Z650 is exceptionally smooth for a

four in-line, particularly at about 70 mph in top gear (equal to 5,500 rpm.)

This makes it very relaxing to ride at speed, particularly as there is

hardly a hint of 'cammyness' with ample response throughout the range.

Power characteristics like this usually result in above average fuel

economy, but although the six-fifty four could return 52 mpg around town,

the overall test figure of 46-5 mpg was lower than expected, but doubtless

due to the heavy consumption of 34 mpg during the performance testing.

Range on the 3£ gallon fuel tank is between 150 and 160 miles.

Although Kawasaki claim the machine will run on unleaded fuel like the

Z1000, in the case of the test bike unless it was run on four-star fuel it

would detonate at small throttle openings when pulling hard. This off-idle

weakness in the mixture strength was probably connected with the Z650's

excessive cold-bloodedness when starting from cold. The process of starting

is made more tricky by the need to disengage the clutch when pressing the

starter button.

Excellent though the machine is on the track or when ridden hard, the Z650

is not quite so impressive when the going is more relaxed. At low speeds,

for example around town streets, the gearchange hangs up and is very clunky,

particularly when engaging bottom gear from neutral. On the open road, the

gearbox which is identical to the unit on the Z750 twin, is by contrast as

slick and crisp as you could want.

Town riding is further spoiled by the excessive backlash in the gearbox,

which is compounded by that stuttering in the carburation.

Being much smaller and more compact than the Z1000, the Z650 has none of

the bigger model's awe-inspiring bulk, and it is a markedly better handling

machine. Although the suspension is softer and more comfortable than the

big model one can skim through bends much more confidently than the Z900 or

Z1000 would ever allow, and with none of the gut-churning high-speed

wobbles that still mark the Z1000 as a bike to be respected when the going

gets hot.

The main improvement on the Z650 is a stiffer frame with more sensibly

designed steering geometry. The rake of the front fork has been pulled back

to 63 degrees, in line with the Z750 twin, and combined with more trail.

The bike is very stable in fast bends, while at low speeds there is only

the slightest hint of 'oversteer' - that feeling that the bike wants to

drop further into a corner - and unlike the Z900 it does not want to

straighten up when cranked over in fast corners.

Ground clearance is enhanced by use of one silencer either side and the

only limitation on the amount you can crank the bike over is the grip of

the Dunlop Gold Seal tyres. If you manage to touch down the left side

projection of the main stand you are a long, long way over.

Harder riders will prefer stiffer springs on the Z650, for although it is

very much a sporting bike, the suspension has been tailored to have a

broader appeal. The 100 lb/in rear springs give a smooth ride and the

dampers are fairly well matched - like the front fork.

H owever, there is still some of the vagueness in the overall feel of the

machine that puts it not quite on par with the best handling roadsters now

available.

Like the GS750 Suzuki, the Z650 has been well planned for the rider. The

seat is soft yet secure enough to prevent you moving about, and the

footrests are well tucked in.

The lowish handlebar is properly swept back at the right angle and can be

adjusted to taste even though the wiring runs neatly through the tubing.

Only general criticism of the Z650 is that the shortness of the bike will

put off taller riders. Cruising at anything over 70 mph becomes tiresome

after only a few minutes due to the height of the handlebar grips.

Along with practically all other Japanese bikes the Z650 has a

stainless-steel, front-brake disc which is fine when dry, but always has to

be allowed for when wet and cold. Kawasaki sensibly resisted the

fashionable temptation to fit another to the rear wheel, and retain a 7-in

drum brake. This works admirably, the brakes being neither too grabby nor

under-powered.

Electrical equipment, apart from the headlamp, is first class. A high power

280-watt alternator supplies all the needs of the system and the battery

never went limp after days of slow commuter riding. Indicators are large

and bright. However, the headlamp suffers from being indistinct and lacking

in penetration on both dipped and main beam.

The heart of the Z650 is its modern power unit. Quiet and unobtrusive, it

whispers along with hardly a rustle from the valve gear or exhaust. At 70

mph in top the engine is barely audible above wind roar. Designed

specifically with quietness in mind, it shares more in common with Honda's

CB500 four. Unlike the Z1000 with its roller bearing crankshaft and gear

primary drive, the Z650 uses a plain bearing crank with a Morse type chain

running to a shaft between the crank and the clutch, which is driven by

gears. For longevity, the valves are opened by twin-overhead camshafts and

bucket followers and although the Kawasaki service book says that valve

clearances need checking every 3,000 miles, it is claimed that they will

not need attention until four times that distance. That is just as well,

for the camshafts need to be lifted to vary the 47p shims under the buckets.

Longer servicing intervals are becoming more and more common; details like

the sight window on the engine to check oil level ease the work. The rear

chain, although very costly, pays its way by lasting up to 700 miles before

needing adjustment thanks to the use of O-rings to keep the oil in the

links and the dirt out.

Undoubtedly, the Z650 is the best Kawasaki so far. It restores the image of

thundering power and speed with a new one of civilised restraint. The Z650

can afford to be sober in appearance because it takes on the 750s and just

about equals them at their own game.

Road Test 1976

Kawasaki Z650 LTD 1978

| Основная информация |

| Модель: |

Kawasaki Z650 LTD |

| Год: |

1978 |

| Тип: |

Классика |

| Двигатель и привод |

| Рабочий объем: |

652 см3 |

| Тип: |

Четырех цилиндровый рядный |

| Тактов: |

4 |

| Мощность: |

65.00 л.с. (47.4 кВт)) @ 8500 об./мин. |

| Крутящий момент: |

5.7 kg-m @ 8500 rpm |

| Компрессия: |

9.5:1 |

| Диаметр х Ход поршня: |

62.0 x 54.0 мм (2.4 x 2.1 дюймов) |

| Клапанов: |

2 |

| Контроль топлива: |

DOHC |

| Карбюратор: |

4x 28mm Mikuni |

| Охлаждение: |

Воздушное |

| Коробка передач: |

5 скорости |

| Привод: |

Цепь |

| Скорость и ускорение |

| Макс. скорость: |

178.0 (110.6 mph) |

| Прочее |

| Вместимость бензобака: |

16.5 л. |

| Вес: |

215 кг |

| Передняя покрышка: |

3.25-19 |

| Задняя покрышка: |

4.00-18 |

| Передний тормоз: |

Двойной диск |

| Задний тормоз: |

Один диск |

Kawasaki Z650SR

|

Основная

информация |

|

Модель: |

Kawasaki Z650SR |

|

Год: |

1979 |

|

Тип: |

Спорт-туризм |

|

Двигатель и

привод |

|

Рабочий

объем: |

652 см3 |

|

Тип: |

Четырех

цилиндровый рядный |

|

Тактов: |

4 |

|

Мощность: |

65.00 л.с.

(47.4 кВт)) @ 8500 об./мин. |

|

Компрессия: |

9.5:1 |

|

Диаметр х

Ход поршня: |

62.0 x 54.0

мм (2.4 x 2.1 дюймов) |

|

Клапанов: |

2 |

|

Контроль

топлива: |

DOHC |

|

Охлаждение: |

Воздушное |

|

Коробка

передач: |

5 скорости |

|

Привод: |

Цепь |

|

Скорость и

ускорение |

|

Макс.

скорость: |

178.0 (110.6

mph) |

|

Прочее |

|

Вместимость бензобака: |

14 л. |

|

Передняя

покрышка: |

3.50-19 |

|

Задняя

покрышка: |

130/90-16 |

|

Передний

тормоз: |

Двойной диск |

|

Задний

тормоз: |

Один диск |

Cycle Guide of 1979

But to enjoy the ego-building benefits of the Saturday

Night Specials, their riders traditionally have had to accept a multitude of

less-welcome qualities. High prices, dubious construction and sloppy fit were

the hazards facing the real do-it-yourself custom builder. Factory-built "Customs"

and "Limiteds" assured good quality and proper assembly but carried even stiffer

prices than building your own one-off special. And no matter what the origin

form never seemed to follow function on these sleek-looking profilers. Those

rakishly stepped or smoothly swooping seats were only tolerable if the burger

establishments were close together. Auspiciously angled handlebars often made

precise control awkward. Pint-sized fuel tanks sometimes dried up before the

next gas station appeared. Cosmetic flash all too often called for a number of

compromises in handling, maintenance, even performance.

Kawasaki first ventured into the customized field with the

KZ900LTD, a bike with more flash than function. The LTD went for about $1000

more than the standard KZ900 and was considerably less versatile, albeit much

more eye-catching. But with the limited-production KZ650 SR, the latest of

Kawasaki's factory-built, custom-like boulevard buzzers, the company has created

a flash-cycle which will provide pleasure for more than profiling. Although the

650 SR has received a full complement of chopper-esque styling touches from its

wide, 16-inch, flat-black-and-polished alloy rear wheel to its bobbed and

pin-striped front fender, the stylists apparently remembered that after the

ogling is over, someone has to actually ride the motorcycle.

For example, consider comfort, one of the most-often

sacrificed aspects of semi-chopped boulevard cruisers. Look at the SR's

carefully styled seat which recalls Triumph customs and yet still complements

the Harley-like suggestions in the tank and rear wheel. When you're done looking,

you can climb on and know that it will be over two hours before the saddle even

begins to feel stiff. The handlebar looks right but isn't radical enough to ever

cramp your arms or bend them at awkward angles. The lean-look front fork glides

smoothly over most bumps and the rear shocks keep the ride comfortable, too.

Only the short front fender reflects a comfort compromise for styling, and then

it's noticeable only on wet streets where more water than usual is thrown up by

the front tire.

The only real comfort concern is a minor one that isn't

related to the custom flavor of the KZ650 SR. The mild vibration which buzzes

the handlebar noticeably and blurs the mirrors slightly at highway speeds is

subdued enough that just wearing heavy gloves will muffle it.

The tiny, peanut-shaped fuel tanks on most customized

street machines go well with the theme of short-range comfort. But the SR's

distinctive fuel tank offers a 3.8-gallon capacity, only .7 gallons less (about

27 miles less range) than the standard KZ650. The SR's tank permits the rider to

go about 120 miles at our average of 38.5 mpg before he has to fish for reserve.

That's enough gas to span the gaps between even the most remote gas stations and

to get farther than most riders will choose to go without a break, even on a

bike as comfortable as the SR. A few miles before you must switch to reserve, a

"Fuel" light in the tach glows until you refill.

The SR uses the same 652.1-cc doubleoverhead-cam

four-cylinder four-stroke engine as the standard KZ650. The internal

specifications are identical, as is the hank of 22-mm Mikuni slide/needle

carburetors. The torque and horsepower charts in the 650 shop manual claim that

the SR has fractionally less power than the standard KZ, although the only

difference between the two is the SR's 360-degree, crossover-style exhaust

system. This system should deliver more power than the standard pipes, but

evidently it doesn't.

The power difference is not perceptible in actual riding,

however. If anything, the SR comes off as a better performer than the KZ. The

engine makes excellent wide-range power and it's easy to ride with very little

gearshifting. Despite a slight lag in throttle response when the throttle was

suddenly pegged at cruising speeds, our KZ650 pulled away from a Suzuki GS750 in

fifth-gear and fourth-gear roll-on acceleration contests starting at 50 mph. The

SR doesn't have as much peak horsepower as the GS750, which the Suzuki

demonstrated by pulling away when both machines began accelerating against each

other in third gear at highway speed. But the Kawasaki has easily obtained

acceleration for passing and more convenient power when dealing with city

traffic.

At the dragstrip, the SR was almost four tenths of a

second quicker and over two mph faster than the KZ we tested in December 1976.

The difference was almost certainly due to the SR's 16-inch rear tire with its

big, wide footprint. The extra rubber on the road prevented excessive wheelspin

and provided more drive for a best run of 13.06 seconds with a top speed of

100.1 mph. We also suspect that the fat rear donut will last longer than the

comparatively skinny 18-inch tires used on the back wheels of most big street

bikes.

The fat rear tire doesn't make the bike track differently

in corners. but it may be responsible for the Kawasaki's pronounced rain-groove

wiggle. Both of the SR's tires grip the pavement well, although the lower height

of the rear of the bike caused by the shorter rear tire contributes to the SR's

slight lack of cornering ground clearance when compared to the standard 650 four.

Even so, the SR offers reasonable cornering clearance, and the folding footpegs

are the first thing to grind, followed by the centerstand on the left.

The SR's suspension offers a comfortable ride, but it's

not 'quite as good in serious swoops and bends as most other current suspension

systems. With 1500 miles on the odometer, the rear shocks on our machine were

beginning to show the first signs of fading away. The minor suspension

shortcomings probably contributed to the only quirk we noticed during fast

cornering. If subjected to a sudden change in suspension load or if whipped

quickly from one side to the other in a tight essbend, the SR would sometimes

react with a small, unalarming twitch. Despite a very slight pogo-stick behavior

in the suspension when cornering aggressively, the 650 was stable, precise and

predictable.

The center of gravity isn't too high, so the SR may be

pitched into a corner with very little effort. In spite of the minor increase in

rake and trail which came about when the rear of the bike was lowered from the

standard bike's specs by the 16-inch tire, the SR was also easy to ride at low

speeds. where steering was still quite light. What's more, surprisingly little

exertion was required to lift the 482-pound machine onto its centerstand.

Although the dual-disc front brake is almost certainly

fitted for its visual appeal, it's also a much more effective (although heavier)

stopper than the standard KZ's single-disc front brake. The dual-disc setup is

controllable, progressive, fade-free and powerful. That power enables the rider

to lock the front wheel at any speed, but never unexpectedly.

The rear wheel's single disc is also capable of locking up

the rear wheel, and on a bike with a narrower rear tire the brake would be too

easy to lock unexpectedly. This is another instance where that wide,

chopper-style rear tire and wheel improves the bike's performance, since the

tire has enough traction to keep the brake from overpowering it. The power of

both brakes and the rear tire's traction enabled the SR to screech to

better-than-average controlled-condition stops and quick, controllable panic

stops in traffic.

Riders who buy the KZ650 SR to show it off at burger

emporiums will probably be disappointed if theirs, like ours, seeps oil and

develops a layer of mung around the base gasket and crankcase breather. Still,

even though the bike smoked during the minute or so of choke-on warm-up which

was required every morning, we never had to add oil. One chain adjustment was

necessary during the first 1000 miles, hut no other maintenance was required.

Despite the SR's macho appearance, the bike has an

ineffective horn which sounds like it belongs on a moped. Fortunately, the

lighting engineers were more safety-conscious than those who chose the horn.

Honda-style always-on running lights incorporated into the front turn signals

make the bike much easier to see and identify in nighttime traffic and help keep

drivers from overlooking the bike and cutting it off. The four-way flashers also

make the SR more visible when necessary.

We're always mildly aggravated by Kawasaki's starter

interlock, which requires the clutch lever to be pulled in before the electric

starter will operate. This is intended to prevent inattentive riders—who don't

check to see if the bike is in neutral before starting—from punching the starter

button while the bike is in gear and on the side-stand, thereby causing the

machine to lunge forward and topple over. Unfortunately, Kawasaki's system

misses the point. An inattentive rider will just get in the habit of grabbing

the clutch lever when he walks up to the bike to start it. Then unless he checks

for neutral, the bike will lurch forward off the sidestand when the engine

starts and the clutch lever is released. What's more, since the rider has to

hold the clutch lever while the engine is cranking, he can't play with the choke

lever to find its optimum setting during cold starts. He has to release the

clutch lever, re-set the choke, then grab the clutch again. And if he has

something like a helmet in his hand when he walks up to the bike he has to put

it down before he can start up.

The SR's clutch disengages with a light pull and engages

smoothly and progressively during normal starts. However when subjected to

full-throttle, high-rpm starts the clutch would grab and make a groaning sound.

The well-staged five-speed transmission functioned

perfectly. Shifts were light, and it was impossible to find false neutrals, even

when we tried. However, locating the real neutral when we wanted it was easy

with Kawasaki's automatic neutral finder. When the 650 is at a stop, it won't

upshift past neutral after you select first gear. Once rolling, the bike shifts

normally again.

Heavy styling treatments are nothing new, even on Japanese

bikes. The mid-sixties street-scramblers, for example, were more styling than

function. What is new is a heavily-styled street-custom which hasn't forgotten

function in an effort to raise its stare ratio. The Kawasaki KZ650 SR is not

only as good, as practical and as complete as its less-striking standard

counterpart, it's functionally better in some important ways, like its rear tire,

dual-disc front brake and maintenance-free cast wheels. And at $2395, the extra

features and flash of the SR will set the buyer back just $470 more than the

standard KZ650.

We suspect that the KZ650 SR will attract buyers

mostly because of its custom appearance and its promise of prowess on the

cruising circuit. But the owner won't regret his choice when he decides to cut a

few hot ones on a meandering back road or when he heads across the country on a

summer tour. The Kawasaki KZ650 SR is undeniably a good-looker, made for turning

heads and showing off. But more importantly, it's also a terrific all-around

motorcycle.

TECH PROBE

A customized motorcycle is supposed to be a

personal statement made by its owner. If that's really true, designing a

mass-produced custom bike must be about as analytical as a fast and loose game

of Pin-the-Tail-On-the-Donkey.

From the outset, the basic concept is a contradiction in

terms. A motorcycle that is identical in every respect to thousands of others

rolling off the same assembly line certainly can't make a statement of a very

personal nature. And unlike the one-of-a-kind bikes hand-built by individual

riders, a factory-designed custom cannot violate the laws governing motorcycle

equipment or even encroach upon the intent of those laws. The machine must be

built well within certain legal engineering parameters. And that stipulation

automatically keeps designers from venturing very far from conventional limits.

Bearing those facts in mind, it should come as no surprise

that the KZ650 SR really isn't a custom in the purest sense of the word. It is a

limited-production motorcycle that offers a few features one might see on a real

custom, accompanied by a number of other pieces that make the bike look

different from the standard model. But more to the point, the SR is aimed at a

specific type of rider, a person who would like to own and ride a fairly

individualized bike but hasn't the time, the equipment, the ability or the

inclination to build one himself. So if he's willing to sacrifice his demands

for total individuality, Kawasaki can supply him with two models that almost fit

his specification. One of those bikes is the KZ1000. LTD. The other is the KZ650

SR.

Scratch the SR more than skin-deep and you'll find a

regular KZ650 lurking beneath the surface. The engine, the entire frame and most

of the suspension pieces are standard KZ650, as are virtually all the internal

pieces.

The engine is an air-cooled, four-stroke,

double-overhead-cam four displacing 652 cc. The bore/stroke relationship is

oversquare, which simply means that the 62-mm bore is wider than the 54-mm

stroke is long. The compression ratio is 9.5:1, rather high by current

street-bike standards, but Kawasaki nevertheless okays the use of unleaded gas.

The 650's dual cams push directly on the ends of its

valves without the aid of any rocker arms. This is a common arrangement on

twin-cam motorcycle, engines. The 650 is the only bike engine, however, in which

the shims used for adjusting the valve lash are housed under the tappet cup atop

each valve stem. Usually these shims are held in a special recess on the top of

each cup. Kawasaki's experience with valve adjustment is definitely more

difficult than with conventional screw-type rocker-arm adjusters, but it can be

done without removing the cams. Because of the valve shim installation in the

650, the cams must be removed so you can get at the shims to change the valve

clearance. And that means re-timing the cams and fiddling with the endless cam

chain when you're done adjusting. It's not the kind of a job a rider would want

to try in his driveway. Actually, it's not the kind of a job an average rider

would want to try at all, which means his bike must visit a dealership to have

the valve lash corrected. Thankfully, KZ650s have demonstrated an ability to go

a long way between valve adjustments, so the valve-shim problem should not be

encountered more frequently than every 10,000 miles or so.

The 650 gets its sparks from a conventional dual-point,

dual-coil, battery-ignition system. The points are opened by a single-lobe cam

driven by the right end of the crankshaft. A flyweight-type mechanical advance

built into the cam advances the ignition spark as the rpm rises.

Although there is nothing wrong with breaker-point

ignitions, they do need periodic adjustment and component replacement. Yet there

are some bikes that have maintenance-free ignitions as standard equipment–either

points-free capacitive-discharge or transistor-controlled systems. And when you

consider the maintenance requirements of breaker-point ignition, the complicated

valve adjustment and the synchronization of four 22-mm Mikunis, the KZ650 earns

the dubious honor of being motorcycling's most difficult and time-consuming

four-cylinder engine when tune-up time arrives.

All is not lost on the maintenance front, however; the

KZ650's crankshaft, connecting rods and all its crank bearings are cheap to

replace or repair. Some big fours use one-piece crankshafts and split-type plain

bearings all around. Others have built-up, pressed-together cranks fitted with

roller and needle bearings. The KZ650 uses a plain crank, just as rugged as the

roller type, that runs a little more quietly and, perhaps best of all, is less

expensive to repair. Roller cranks usually must be replaced as a unit–bearings,

flywheels, connecting rods and all–but just one bearing or rod of a plain crank

can be replaced. And completely overhauling it is much cheaper than with the

roller style

Source Cycle Guide of 1979

1_m.jpg)

_m.jpg)

1982.jpg)

.jpg)